Right about the time a nurse hands you your swaddled, screaming baby for the first time, all of the things you don't know about newborns suddenly come rushing to the fore. You might have expected to feel amazement at the first sight of your newborn. But were you expecting surprise -- or even shock? Your newborn may have some unexpected physical attributes, like lanugo (a fine, downy hair that covers an infant's body in the womb), a conically-shaped head, or bright red birthmarks. In addition, you may be disturbed when your baby's eyes move independently of one another.

The good news is, all of these "imperfections" will usually disappear in the first weeks of your newborn's life. But it might be helpful to prepare yourself for the surprises still to come. In this article, we will help you understand your baby's growth and development during his/her critical first year in the following topics.

Advertisement

- Appearance of a Newborn What does a newborn look like? They might not all look like the little round-faced angle you imagine. On this page, we will detail the physical characteristics your infant may display. The appearance of a newborn's head and hair are described along with a feature-by-feature examination of his face. You'll also read about the appearance of yellowish skin (jaundice), rashes and birthmarks and how to treat them. Plus, we explain the newborn body's unique proportions and traits. Your newborn's appearance might be a surprise, but babies come in wide range of normal shapes and sizes.

- Reflexes and Responses of a Newborn A human baby's innate knowledge allows it to turn its head, suckle, grasp your finger, and cry out when startled. There are several other lesser-known newborn reflexes, like the Babinksi and Moro, that are described in this section. You'll also find a discussion of the newborn's unique responses to you and to the environment, and some helpful information on how you should respond to your infant's cues. You will be amazed with some of the behaviors your baby is born with and how they help him survive his first few days.

- The Newborn's Five Senses When a baby emerges from the womb, he/she already has the capability to see, hear, taste, touch and smell. This section features an in-depth account of each of baby's senses, and how they are affected by various stimuli. You will learn how developed your baby's senses are at birth and how quickly they will develop. We also include suggestions for providing your newborn with visual stimulation to aid in their development. Before you go out and buy a new mobile, makes sure you know which patterns babies enjoy.

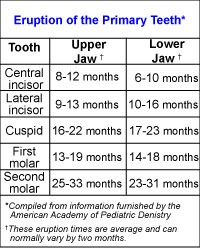

- The Newborn's Growth and Teething Imagine this: during the first three months of life, babies will gain an average of an ounce a day, or about two pounds a month. That's a lot of pounds to be packing on! On this page, we will talk about your newborn's birth size and the rate at which he/she will grow in the first year. Plus, we'll tell you about teething. We'll let you know when to expect that first tooth and how to cope with some of the pain your baby will feel as their teeth grow in. We'll also let you know what kinds of foods your baby's new teeth can handle.

- The Newborn's Physical Development: Gross Motor Skills A newborn enters the world with virtually no muscle control. They can't hold their heads up on their own and they can't even roll over. In this section we'll introduce you to the basic principles your baby's physical skills develop according to. We'll focus on the gross motor skills, including rolling over, sitting up, crawling, standing and walking. You'll find descriptions of each skill's progression from first attempts to mastery. Before you know it, your baby will be zooming around the house.

- The Newborn's Physical Development: Fine Motor Skills Your newborn's hand-eye coordination develops slowly but surely, beginning with the simple realization that the hand is attached to the body. As your baby becomes more graceful and coordinated, he or she will move through many phases including passing objects from hand to hand, grasping and releasing, swiping and poking. This section contains an outline of baby's fine motor skill development by age from birth to 14 months. You will learn when your baby will be able to bring their hands together and when they will be able to scribble and draw.

If you'd like to learn about your newborn's characteristics and development, turn to the next page to get started.

This information is solely for informational purposes. IT IS NOT INTENDED TO PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE. Neither the Editors of Consumer Guide (R), Publications International, Ltd., the author nor publisher take responsibility for any possible consequences from any treatment, procedure, exercise, dietary modification, action or application of medication which results from reading or following the information contained in this information. The publication of this information does not constitute the practice of medicine, and this information does not replace the advice of your physician or other health care provider. Before undertaking any course of treatment, the reader must seek the advice of their physician or other health care provider.

Advertisement