In this section, we'll examine the myriad technical and artistic challenges that were encountered -- and overcome -- by the "Finding Nemo" crew in creating the sights and sounds of the movie.

How Technical Challenges Were Overcome

"Finding Nemo" marked another milestone for the technical art of computer animation.

"Technically, we've pushed things beyond anything Pixar has done before," says executive producer John Lasseter. "Just animating fish was difficult, but our technical team has created an underwater environment that is graceful and beautiful. The real underwater world is so spectacular that it's already a fantasy world. Our challenge was to let the audience know that our ocean is caricatured, so our goal was always to make things believable, not realistic. By stylizing the design of things, adding more geometry and pushing the colors, we were able to create a natural and credible world for our characters."

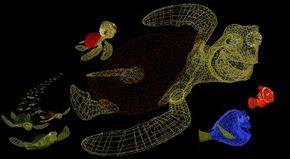

Brian Green, the characters CG supervisor, explains, "This was the first time that Pixar had a character department, and it allowed us to serve the animators' needs better. The animation buddy might give us a drawing and say, 'For acting purposes, I need it to look more like this.' We would go in and adjust it. This made for a very close relationship. We also tried to create automatic dynamic motion for some of the characters. Our goal was to try and automate everything we could -- things like the movement of dangly bits on some characters -- so the animator could concentrate on the performance."

To do this, the Pixar animators had to be more innovative than ever before.

How the Production Design and Cinematography Work:

The Look of "Finding Nemo"

From a visual standpoint, "Finding Nemo" is a stunning achievement that is both aesthetically appealing and groundbreaking.

The animation team previously had their share of challenges bringing life to toys, bugs, and monsters, but their assignment on "Finding Nemo" proved to be the toughest yet. Visits to aquariums, diving stints in Monterey and Hawaii, study sessions in front of Pixar's well-stocked 25-gallon fish tank, and a series of in-house lectures from an ichthyologist (a biologist who specializes in fish) all helped to get the animators into the swim of things. They also became trained scuba divers and made several research diving trips and a visit to Sydney Harbor to get the lay of the land and sea.

The animators studied Disney classics that involved underwater scenes -- "Pinocchio," "The Sword in the Stone," "Bedknobs and Broomsticks," and "The Little Mermaid" -- for inspiration. "We kept coming back to 'Bambi' because of the way the filmmakers adhered to the real nature of how these animals moved and what their motor skills were," says director Andrew Stanton, also noting the film's impressionistic style of blurred backgrounds -- just like it really is underwater. "We thought of it as 'Bambi' underwater." This gave the film a realistic look, and helped focus on the characters.

"The film begins with an intense Garden of Eden coral reef," says production designer Ralph Eggleston. "From there, the underwater backgrounds tend to become more impressionistic with just a mountain or sandy bottom in view."

Supervising animator Dylan Brown, an eight-year Pixar veteran, and directing animators Mark Walsh and Alan Barillaro were responsible for guiding an animation team that fluctuated between 28 and 50. With a large cast of characters -- ranging in size from a petite cleaner shrimp, Jacques, to the enormous blue whale -- the animators had their work cut out for them as they learned about fish locomotion and discovered how to create believable behaviors for characters lacking arms and legs.

"Each film has its own unique set of challenges, and we always begin by trying to figure out what they are and how to solve them," Brown explains. "With 'Nemo,' we had an entire cast of fish characters with no arms or legs. Since they didn't have the traditional limbs to allow strong silhouettes, we had to invent a whole new bag of tricks. We put a lot of work into the face and getting the facial articulation just right, and their faces had to be integrated with the entire body language."

Timing was another big factor. "With characters like Buzz, Woody, or Sulley [from previous Pixar films], you have an earth-based gravity," says Brown. "But fish underwater can travel in a flash. You blink and it's gone. We wondered how they did that and studied their movements on video. By slowing things down, we could figure it out and learn how to get our fish characters from one place to another in a frame or two. We always tried to incorporate naturalistic fish movements into the acting by using one-frame darting and transitioning from place to place. It made the characters very believable."

In the past, animators were always told to "ground their characters" and avoid letting them "float." With "Finding Nemo," they had to do the exact opposite. Barillaro says, "It was fun and challenging to come up with how they could communicate and gesture. Without gravity to deal with underwater, we would have a character drift a bit when he gestured. I found that a lot of the gestures humans make could be boiled down to eye and face movements. I would look at my own face in the mirror and imagine I had a tail on the back of it."

"The music, the color, and the lighting are the things that really give the underlying emotion of every scene," says Lasseter. "And the lighting and color in 'Nemo' is always used for storytelling. Ralph Eggleston is a master at that, and Sharon Calahan knows how to get that on the screen."

How Science and Imagination Worked Together in Creating "Finding Nemo"

Helping the animators get up to speed on fish behavior and locomotion was Adam Summers, a noted professor in the Ecology and Evolution department at the University of California at Irvine.

"I'm what is called a biomechanic or sometimes a functional morphologist," says Summers. "My specialty is applying simple engineering principles to how animals move and eat." Pixar asked him to tell the Pixar staff about things like fish shapes and colors, and Summers ended up teaching them a graduate-level ichthyology course of 12 lectures. "They were infinitely curious about fish, and they were flat-out the best students I had ever had. By the end of each lecture, they would be asking me questions that I didn't have answers for."

Character designer Ricky Nierva asked where the eyebrows were. Summers says he told him, "They don't have eyebrows. They don't have any muscles in their face except for jaw closers. So Ricky said, 'Adam, fish don't talk but talking is going to be a requirement for the movie. So we're going to have to be taking artistic license with science all the time.'"

Summers also gave the character designers and animators some important insights into fish movement. "In most animated films with fish, the characters move back and forth with no visible propulsive device, and that really offends the eye," Summers says. "You don't need to be an ichthyologist to know there's something wrong."

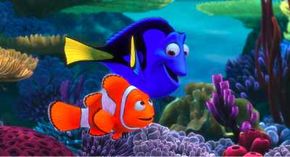

So Summers explained the difference between fish fins like "flappers" and "rowers." "Clown fish are rowers who tend to propel themselves by moving their pectoral fins in a horizontal motion. At higher speeds they wiggle their entire body," he says. "Blue tangs, like Dory, are flappers who flap their fins up and down to move and almost never wiggle their entire body. The result was that Father's movements were more fluid and graceful, while Dory tended to flit sharply about."

When a fish moves in 'Nemo,' its fins are moving, too, giving it a natural feel. "They did a heck of a job making clear the differences between living in an incompressible fluid like water and compressible fluid like air," Summers says. "I was completely knocked out."

How the Underwater World of "Finding Nemo" Was Created

Under the watch of supervising technical director Oren Jacob were six technical teams specializing in different components and environments seen in the film. Lisa Forsell and Danielle Feinberg were the CG supervisors responsible for the Ocean Unit. David Eisenmann and his team handled the models, shading, lighting, simulation, etc., for the Reef Unit. Steve May headed up the Sharks/Sydney Unit, which tackled the submarine scene, shots inside the whale, and most of the above-water scenes in the Harbor. Jesse Hollander oversaw the Tank Unit, which created all the elements for the fish tank. Michael Lorenzen was in charge of the Schooling/Flocking team, which created hundreds of thousands of fish, plus key elements for the turtle-drive sequence. Brian Green led the Character Unit, which created the look and complex controls for nearly 120 aquatic, bird, and human characters.

The Ocean Unit was responsible for such scenes as the school of moon fish, which form different objects (an arrow, a lobster, a boat, etc.), the angler fish chase, and the turtle drive in the East Australian Current. The unit's most challenging and impressive scene, however, was the jellyfish forest. This rich and colorful moment finds Marlin and Dory in an ever-expanding and increasingly dangerous sea of deadly pink jellyfish.

Forsell explains, "This scene involved several thousand jellyfish. Our unit built the model for a single jellyfish and put a lot of work into the build-up of jellyfish density. This involved creating a simulation for the group that controlled the movement of the tendrils, how quickly they swam and in what direction. We had some great reference footage and were particularly fixated on one species from Palau that we found at the Monterey Aquarium. David Batte wrote a whole shading system we called 'transblurrency.' Transparency is like a window and you can see right through it. Translucency is like a plastic curtain that lets light through but you can't see through it. Transblurrency is like bathroom glass: You can see through it, but it's all distorted and blurry."

Water has traditionally been one of the most difficult things to create effectively and economically in computer animation. Faced with a film that was set largely underwater, the technical team on "Finding Nemo" had to find new ways to meet the enormous demands of the production and solve some of the problems that had been encountered by others in the past. Jacob led the effort to give Stanton and his team exactly what they wanted.

"Our starting point was to watch a lot of films with underwater scenes and analyze what made them seem like they were underwater," explains Stanton. "It was a bit like getting a great cake and trying to figure out how somebody baked it by breaking it down. We came up with a shopping list of five key components that suggest an underwater environment -- lighting, particulate matter, surge and swell, murk, and reflections and refractions."

Jacob adds, "Even before we had a finished script, we knew we had a story about fish in a coral reef. That was enough for our global technology group to begin coming up with tools for making water move back and forth. Coral reefs are organic living things, so it's not a static set like the door vault in 'Monsters, Inc.' Early on, we took a diving trip to Hawaii with some of the film's key players. Then we looked at every Jacques Cousteau, 'National Geographic,' and 'Blue Planet' video we could find. We also studied every underwater film from 'Jaws' and 'The Abyss' to 'The Perfect Storm' to understand what the filmmakers chose to caricature. We came up with our own idea of what audiences expect to see with water and developed our own ratios and proportions."

How The Sound in "Finding Nemo" Works

After the film's visuals are completed, two separate sound departments were responsible for creating what you hear in the movie: music and sound effects. Composer Thomas Newman was hired to create his first epic score, and leading the sound effects team was seven-time Oscar-winning sound designer Gary Rydstrom, who also worked on all the other Disney/Pixar features in addition to Pixar shorts such as the 1989 favorite "Knick Knack."

Newman, a five-time Oscar nominee and an Emmy winner for his theme for "Six Feet Under" (he's the cousin of songwriter Randy Newman, who composed music for the previous four Pixar animated films), was a major inspiration for "Finding Nemo" even before he was hired. Stanton wrote the screenplay for the film while listening to Thomas Newman scores on his headphones, and during the editing process, Newman's previous film music was used in the temporary music "scratch track." Newman's lush, sophisticated score came to be regarded by the filmmakers as a character in the film.

"He does a lot of overdubs, where he'll gather a group of musicians together apart from the orchestra session and have them play lots of interesting percussion and instrumentation," co-director Lee Unkrich explains about the recording process. "Then he'll layer that into the music that's been recorded on the soundstage with the orchestra."

But first Thomas would try out his musical themes by playing them on his keyboard sequencer at his house. "Towards the end of production, we would go down there almost once a week and hear all the music to picture mocked up in his studio," says producer Graham Walters. "By the time we got to the recording sessions, we had heard everything, but it sounded so much better with a 105-piece orchestra. For our film, he also did his signature overdubs, where he goes in with his posse ahead of time and records things to go on top of the orchestral stuff. With the turtle drive scene, the music breaks into a full-on classic surf rock sound."

While the musical score was being written and recorded, sound designer Rydstrom and his "noise" boys created an inventive recorded catalogue of swish and splash sounds to complement the visual excitement of the film and add to the sensation of being underwater.

One of the things Rydstrom's crew discovered early on was that sounds actually recorded underwater were boring, so they manufactured many of their own. "But we did go to a pet store with a lot of aquariums and stuck our mikes in the tanks and moved them through the water," Rydstrom says. "For the fish tank in the film we wanted a contrast with the wide-open ocean. Occasionally, you hear weird, cheesy filter buzzes, goofy bubbles, and things that happen in real aquariums."

Rydstrom recorded sounds in the ocean, in jacuzzis, and even in a coastal cave to get the sound of water sloshing and crashing. The latter ended up being used to approximate the inside of a whale. The sound of Marlin and Dory bouncing on jellyfish proved to be a bit elusive. Rydstrom finally got the desired effect when he bounced his finger on a hot water bottle to get the nice little muted, watery "glug" sound he wanted.

In an apt example of suffering for one's art, a sound design assistant even recorded her own visit to the dentist. The brutal dental drill heard in "Finding Nemo" is actually the assistant getting a filling done.

In the next section, we'll take a close look at the movie's greatest achievement: its characters. .