One of the classic tenets of modern architecture was put forth by American architect Louis Sullivan: "Form ever follows function" [source: Rawsthorn]. What Sullivan was getting at was that the style of architecture and design of any object should reflect its purpose. Sometimes form and function are wed together beautifully; other times, you end up with a very functional item that is not at all attractive. At the opposite extreme, you have a gorgeous object whose highly designed form gets in the way of its function.

There is no place where this last example is more obvious than in women's fashion. Think of 4-inch stiletto heels. Or giant hoop skirts of long ago. These fashions and others are not terribly functional, but make women look attractive – at least according to the standards of their time.

Advertisement

For hundreds of years, women have gone to extreme lengths to look "perfect", and for many that doesn't start with their outerwear like dresses and skirts, but with what's underneath them. To conform their bodies into more desirable shapes, women have turned to special undergarments designed to flatter their figures. These are called shapewear.

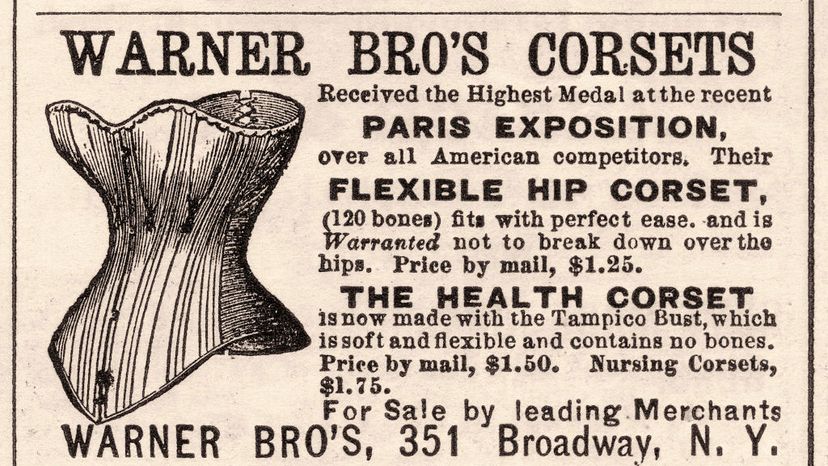

Shapewear – corsets, girdles and the more recent bodysuits – can work miracles. These undergarments can completely change the appearance of a woman's shape by tucking fat away, leading to a shapelier silhouette.

Sadly, fat is not all that shapewear has been known to move. Corsets of the Victorian era were so constrictive they moved wearers' internal organs to the point that their health suffered. Achieving the "perfect" form hurt the overall function of their bodies. Nowadays the situation is not so extreme, but the shapewear industry is still booming as women continue create the ideal body type.

Advertisement